Roaming around St. Louis: A Personal Reflection on the Centre de Recherches et de Documentation du Sénégal and the Struggles of a UNESCO World Heritage City – by Renée Riedler

During my recent visit to Senegal, I had the opportunity to explore the Centre de Recherches et de Documentation du Sénégal (CRDS), located on the southernmost point of the historic Ile de Saint Louis, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2000. Established in 1943 by the French colonial government as the Centre IFAN-Sénégal-Mauritanie, it is now part of Gaston Berger University. One important task of the CRDS is the preservation of its extensive historical photo collection, currently being digitized and continuously expanded through collaborations with local photographers.

Renée Riedler visiting Atelier TIESS in Saint-Louis, Senegal.

A Gallery of Memory: Oumar Ly's Photography

Just a few steps from the CRDS, we visited a gallery featuring the works of renowned portrait photographer Oumar Ly (1943-2016). I vividly remember my visit to his studio in Podor, the northernmost city of Senegal, back in 2017. A family member had opened the studio to visitors and sold postcards. I wondered if the studio and the photo archive still existed, but my colleague Yaelle Biro informed me, standing before one of Oumar Ly’s stunning portraits of a woman, that the photographs had already been sold by the heirs.

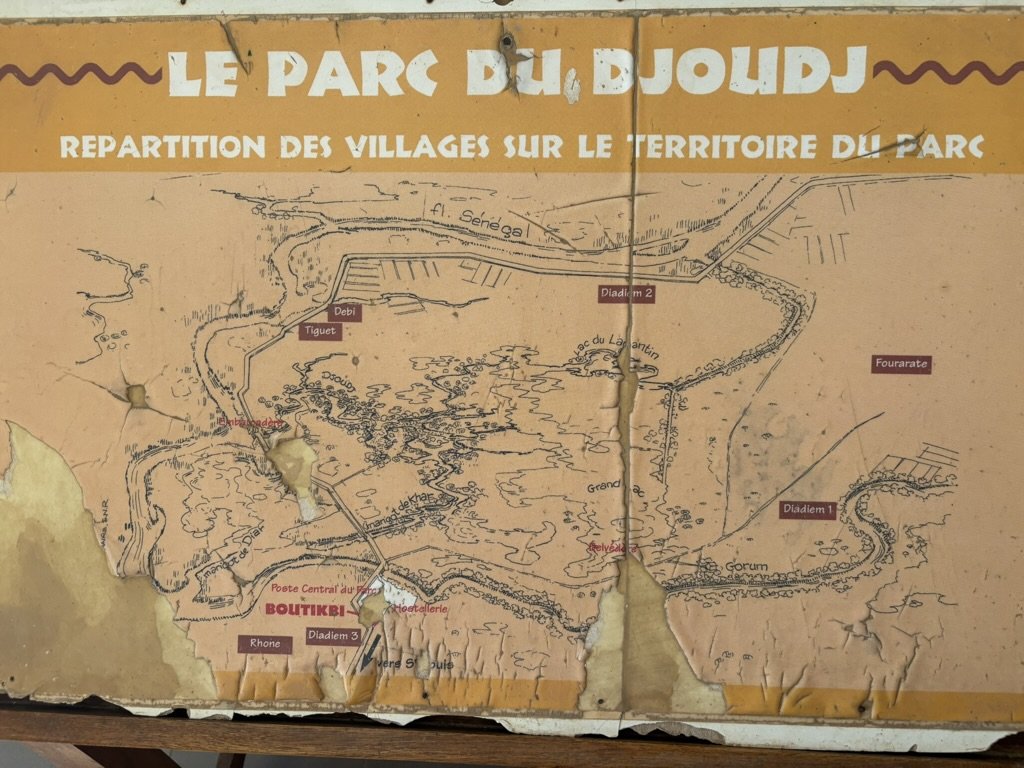

One of the highlights of our visit to the CRDS was when Fatima Fall took us to the rooftop, where we were treated to a breathtaking view of the Senegal River, which has earned the city the nickname "Venice of Africa." To the north, we could see the lively courtyard of the adjacent school and the grid-like arrangement of houses with courtyards and shaded balconies. Some of these houses stood empty after the Mauritania-Senegal border war (1989-1991), when the Mauritanian population was displaced from the city. The lingering tensions from that period are still palpable today, and although the border is within sight, it remains a seemingly insurmountable distance—except, perhaps, for the mobile service provider Orange, which made sure to inform us of the roaming fees while we were at the Djoudj National Park, just to the north of St. Louis.

Historical Insights at the Guesthouse Jamm

We also learned from our French host at the Guesthouse Jamm, a lovingly renovated colonial building on Rue Abdoulaye Seck, about the evolving story of the region. He shared that when natural gas reserves were discovered near the border, the news was met with mixed feelings. However, the countries involved have now reached a peaceful agreement and, since 2024, are jointly sharing the profits from the offshore gas fields with BP, the British multinational oil and gas company.

The Guesthouse Jamm is a testament to the resilience of St. Louis. Unlike many families who have lived on the island for generations, our host had the resources, time, and perseverance to renovate the building in traditional architectural style. The courtyard and rooms are decorated with African sculptures, local handicrafts, and textiles from the Tess Gallery. In the same street, colonial buildings with shops and restaurants sit side by side with collapsed and newly restored red brick structures. Amidst these are modern concrete buildings, reflecting the city’s evolution from the colonial past to the present day, connected to the mainland via the Pont Faintherb.

At Guesthouse Jamm

The Dilemma of St. Louis' Historic Bridge and the Threat of Coastal Erosion

During our time in St. Louis, traffic congestion on the historic bridge was a common sight during peak hours. Our driver expressed frustration, wishing for the construction of an additional bridge. Fatima Fall, however, reminded him that building another bridge would result in the loss of the UNESCO World Heritage status. From the backseat, I couldn’t help but chuckle, as the UNESCO status often sparks similar conflicts of interest back in Vienna.

Yet, it’s not just traffic that threatens St. Louis. The city is in danger from coastal erosion, with many residents of the nearby fishing village of Langue de Barbarie already losing their homes and livelihoods. A misguided construction project meant to redirect seawater flow actually worsened the erosion, and since 2018, the Saint-Louis Emergency Recovery and Resilience Project (SEERP) has been working with the West Africa Coastal Areas Management Program to combat the rising waters.

I couldn’t help but wonder why such a devastating issue—one that affects thousands of people and a UNESCO World Heritage site—was not mentioned during the conference. Perhaps the themes of climate change and conservation could be the focus of a future conference in St. Louis, perhaps in collaboration with the GloCo Project and the University of Vienna.